Rural Utopias Residency: Nathan Gray in Ieramagadu / Roebourne #6

Nathan Gray is currently working with Juluwarlu Aboriginal Corporation and Ngaaarda Media in Ieramagadu / Roebourne. This residency forms part of one of Spaced’s current programs, Rural Utopias.

Nathan Gray is an accomplished Berlin-based sound artist, programmer and broadcaster whose practice is an interdisciplinary one that crosses over into film, video, performance and installation. Gray's recent, meticulously written lecture performances explore historical, technological and social circumstances imagining them as scores for possible futures, alternate histories and radically divergent presents. Often employing sound and video, in which his background lies, these evocative works invite audiences to imagine futures beyond contemporary crises.

Here, Nathan shares an update.

Found in translation.

Language in the abstract

Bear with me, this might be a little long but here I’m going to lay out some of the bigger ideas that my recent residency with Juluwarlu Aboriginal Corporation and Ngaarda Media brought up, and what they might mean for my wider practice.

To me the process of translation is invigorating. Negotiating multilingual environments and using language in the field as opposed to on the page is my main focus these days. It’s a radical shift from my previous practice, but I’m now starting to realise it’s not unrelated.

My older works were focussed on sculptural installation and performance, but these shared some characteristics with how language works. Things that Fit Together (2014), for instance, took everyday objects and recombined them like an alphabet, morphemes or words in a sentence using the simple grammatical rule that no glue, screws or tape were used. My electronic music with Dylan Martorell in the duo Snawklor (ongoing since 1994) uses randomised sets of sounds in similar ways, and the result of this long-term interaction between friends is predictably conversational. The performances I organised of Cornelius Cardew’s Scratch Music (2012 - 2015) used a score to generate outcomes that were, like language, both rule based and socially negotiated. Though it was not the original focus, all of these works share structural similarities with language.

My interest in sound art, linguistics, and experimental language practices is in its abstraction, as something immensely complex yet used without a second thought, so close to thought it is difficult to consider separately. But language is not an ornament - it’s a tool, perhaps a beautiful one, but; in its utility, its practice, is where it’s honed and gains beauty.

2. Language in practice

Juluwarlu’s contemporary archiving methods combine the traditional oral archive embedded in the land with Western written and technological archiving. Traditional Aboriginal techniques of remembering information by linking songs and locations are often referred to as Songlines.

Songline is a Western term and it should be remembered that it is at best a translation. The word refers to a set of practices that are shared by a large number of Aboriginal language groups, but differ from group to group.

I haven’t heard Yindjibarndi people use the word about their own system of lore, rather they refer to Bidarra law, which contains songs linked to places in similar ways. Juluwarlu’s combination of this type of oral tradition with Western written and technological systems of documentation, result in an example of what Indigenous curator Margot Neale calls the third archive, Indigenous and Western archiving methods, combining and adjusting to each other.

Indigenous knowledge is based not only on language, but on language that is designed to be durable. If you’ve ever caught an ear-worm (a song that gets stuck in your head) you’ll know the painful durability of language linked to music. When also linked to places, these songs create indelible impressions that transcend generations.

I recently interviewed a young law man, Ashton Cheedy, who was involved in the running of initiation ceremonies for a large area of the Pilbara. His duties involved learning and teaching songs, many of which were in languages he didn’t speak.

As we sat together he tried to work out how many songs he knew, and eventually settled on the figure of around 200.

In the late 80s when Lorraine Coppin started Juluwarlu, she began by using a domestic tape recorder from Target to record elder Woodley King. The utility of this technology to a people used to handing down stories for generations was obvious. The importance of the law, or Birdarra Law, as The Yindjibarndi call this complete system of knowledge — is not separated into categories, but combines what might be referred to as geographical, astronomical, religious, ecological, legal and artistic information.

In 2018, Yindjibarndi Aboriginal Corporation CEO Michael Woodley sang the Burndud song-cycle for a select section of the court in an exclusive native title hearing on country. The Burndud contains songs that are usually secret to the uninitiated. Another feature of Indigenous knowledge systems, is that not all knowledge is for everyone. Micheal used the performance to demonstrate the importance of country and its centrality to Yindjibarndi knowledge. In this event Birdarra Law entered into the records of Western law.

In August this year a second hearing on country took place - this time on the site of the Fortescue Metals Group’s (FMG) Solomon mine at a gorge called Bangkangarra that the Yindjibarndi have not had access to for over a decade. The Yindjibarndi hoped to demonstrate the cultural impact of FMG’s mining without permission or proper consultation so the court could decide on compensation.

As the Australian Financial Review states, “Fortescue has shipped 1.5 billion tonnes of iron ore from Yindjibarndi land in the Pilbara since production at its Solomon Hub began in 2013, generating $50 billion in revenue. But the $60 billion company is yet to pay a cent to the Yindjibarndi people.”

The landmark compensation hearing is the first time cultural impact is being considered in a native title compensation case, and according to the ABC, it is “expected to set new precedents surrounding economic compensation for cultural losses”.

Destruction of the land in a system where knowledge is tied to the land is destruction of culture.

The fact that traditional songs and stories are once again being entered into the legal record, is to me, a demonstration of the utility of language and the importance of archiving, preserving and revitalising language as a container for the things that are important.

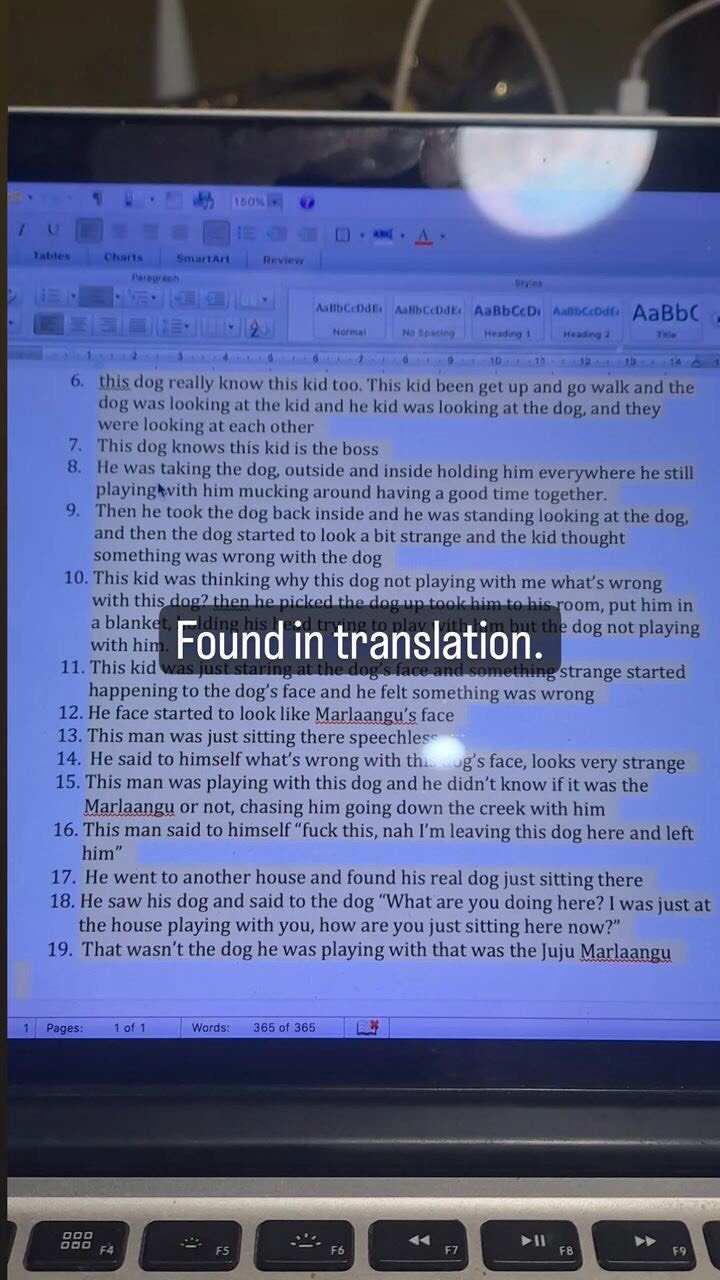

3. The Marlaangu Project

When I began my second residency with Ngaarda / Juluwarlu my project was ambitious.

I wrote a script that was intended to be translated into Yindjibarndi and performed by young people, but I underestimated the time that translation into an Indigenous language takes. There’s no google translate for most Indigenous languages and like many things in community projects, there’s a good deal of negotiation. After many phone calls and emails I realised that the best thing would be to go and sit with elders as they discussed the translation, the work was slow.

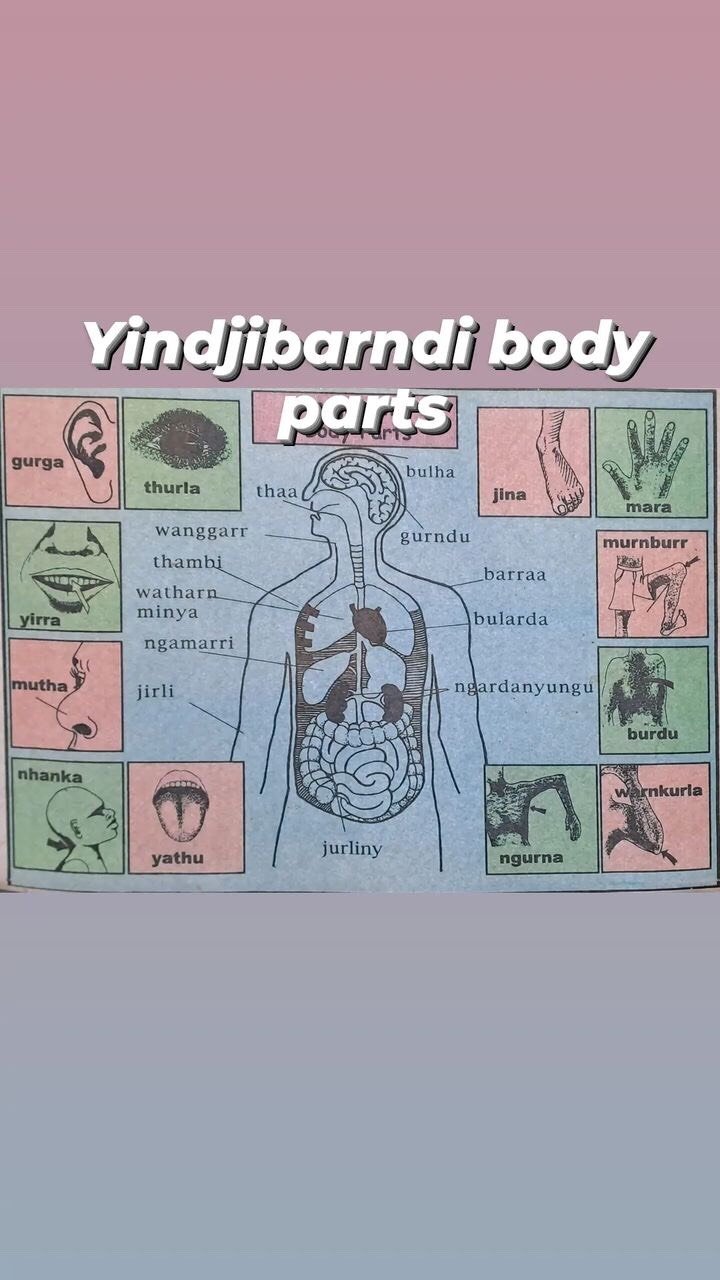

Yindjibarndi speakers want to keep their language free of English words. Rather than borrowing new terms they create translations: car and house already have translations but one of the stories I ended up using has a pivotal moment centred around a cake. Lorraine Coppin had to invent a word, one that roughly translates as “sweet thing”.

It’s an interesting situation. Within English, language is considered to be how people speak rather than how they should speak. But, Yindjibarndi people are fighting to preserve their language and such attitudes, while progressive, are perhaps luxuries only afforded to large or dominant languages.

Contemporary linguistics often looks not at preconceived notions of “correct” language — prescriptive grammar, but at how language is actually spoken —descriptive grammar. The tension is at its peak in the debates around using non-standard forms of English in schools, most notably African American Vernacular English. Teaching in non-standard forms of English is thought to facilitate better educational outcomes in communities in which the nonstandard form is prevalent. This use is often resisted in the belief that non-standard forms are incorrect and recognition of them will lead to an inability to speak standard English or that this recognition will lead to a detrimental change to standard English. Though languages are always changing, and contemporary ideas around code-switching recognise that language is context dependent i.e. that one speaks differently in the pub than in an essay, this debate continues.

While Aboriginal English is becoming more recognised officially, and is possibly the main form of communication of Yindjibarndi youth — it is not used in schools. Yindjibarndi itself, like all indigenous languages in Western Australia, is only taught for half an hour a week. Yindjibarndi elders want to hold onto a pure form of their language, closer to that used in their songs and rituals, and this means not incorporating English terms. Ironically, having a prescriptive attitude to their language is their chosen method of language preservation.

What surprised me while realising the project, Yindjibarndi youth, many of whom speak and understand their language in an everyday context, were not confident in reading or performing in it. Like all 31 languages of the Pilbara, Yindjibarndi is an endangered language. Through the Marlaangu Project we were able to get a better idea of the language skills of Yindjibarndi youth. Hopefully, if my work with Juluwarlu continues, I would like to develop artistic resources in consultation with elders that inspire young people to use their language. The language of Birdarra Law but a language which can be used to speak about contemporary things too.

As I’ve stated before in other blog posts the resulting work - quickly redesigned from my original intentions, collects contemporary ghost stories around the figure of The Marlaangu. In the end the work was spoken by Yindjibarndi people in their 30s and 40s and will be one of only a few contemporary texts in Yindjibarndi. Hopefully the project will contribute to the durability of the language but there needs to be more such texts, as well as more opportunities for people to experience and use their language, not only because it is the basis of their cultural knowledge but because it is beautiful, rich, a source of pride and, as recent legal proceedings have shown: a source of power.

Images courtesy Nathan Gray, 2023.