Rural Utopias Residency: Nathan Gray in Ieramagadu / Roebourne #3

Nathan Gray is currently working with the community of Ieramagadu / Roebourne. This residency forms part of one of Spaced’s current programs, Rural Utopias.

Nathan Gray is an accomplished Berlin-based sound artist, programmer and broadcaster whose practice is an interdisciplinary one that crosses over into film, video, performance and installation. Gray's recent, meticulously written lecture performances explore historical, technological and social circumstances imagining them as scores for possible futures, alternate histories and radically divergent presents. Often employing sound and video, in which his background lies, these evocative works invite audiences to imagine futures beyond contemporary crises.

Here, Nathan shares an update from Ieramagadu / Roebourne.

For the second part of my residency I began working with Juluwarlu art centre and cultural archive to produce a podcast. I’m going to talk about that work-in-progress and some thoughts that arise as I edit the audio and the factors that will contribute to making it unique and distinct from the usual podcast format.

The project began at the suggestion of Juluwarlu CEO Lorraine Coppin who wanted to generate a bigger audience for the biographies of Yindjibarndi elders that were written by Vicki Webb – Juluwarlu’s resident linguist. These biographies form the core of the current exhibition at the Ganilili centre.

We discussed integrating these biographies to present a chronological history that moves between the different voices of the elders and reveals a linear picture of the community’s history from the 1930s until the mid 80s.

The biographies are presented in the first person as autobiographies and are drawn from extensive interviews giving them an unusual feel. Occasionally they incorporate information from outside of the subject’s experience and in the past tense, as when elder Ned Cheedy says “So, during the last years of my life, I worked non-stop with Juluwarlu, sharing all that my Elders had taught me.”

It was also Lorraine’s idea that the various voices would be read by the living descendants of each elder. Obviously this meant non-professional voice actors, recorded in their homes and gardens with interruptions, background sounds and often their own comments on the action that’s happening in the script.

All of these factors disrupt the possibility of a linear history or audio documentary, and these circumstances dictate that the readers don’t impersonate or recreate the elder’s voice exactly but instead blend the elder’s voices with their own. In this work the living community that the elders' hard work and resilience made possible encroaches into the retelling of that history. The past is very tangibly present.

The time period that the podcast deals with is characterised by multiple dispossessions. First, even though the Yindjibarndi stayed on their traditional land, they became unpaid labour for cattle stations. Later, as this system gradually fell apart, they were moved from their land into the reservation just outside of Ieramagadu / Roebourne and then from there into state housing in the town itself.

Even though each step physically distanced them from their land and their traditional lifestyle, the story of that generation is one of maintaining these connections despite the various structural obstacles and coercions. In meeting the descendants of this remarkable generation I got to understand how the current generation of elders, while continuing the work of their ancestors, is remarkable in their own right.

First off I visited Stanley Warrie at Cheeditha. Stanley is the son of elder Yilbie Warrie who had been one of the main Yindjibarndi lawmen and established Cheeditha as an independent alcohol–free community after the government bulldozed the reservation in the 1970s.

Cheeditha’s main income is from its arts centre but in the future it will be supported by the recently established Cheeditha Energy – a corporation that will build a large solar farm bringing energy and income for years to come.

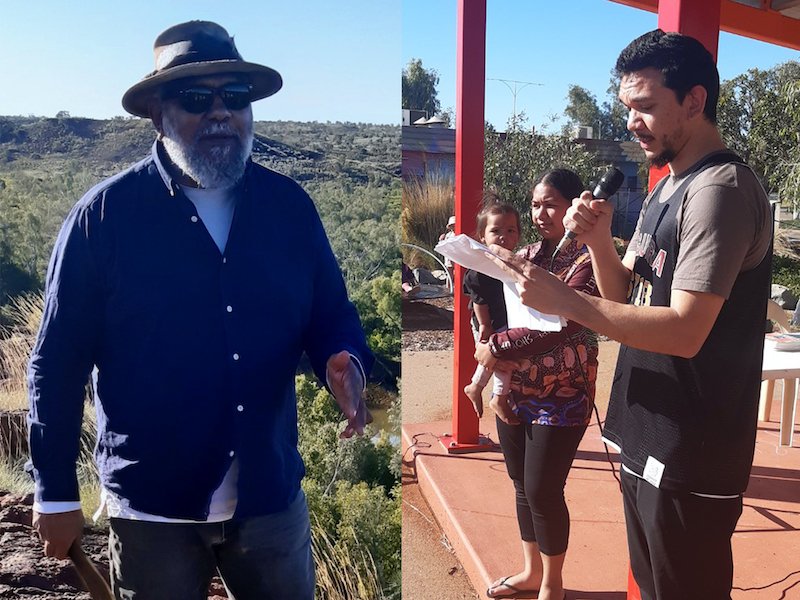

Later I interviewed father and son Michael and Wimiya Woodley, each of whom read from the biography of their respective great grandfathers. Michael is a senior Yindjibarndi lawman and CEO of the Yindjibarndi Aboriginal Corporation. He read from the biography of Wimiya King – a master weapons maker who preserved his ties to the country by riding his bicycle hundreds of kilometres to collect materials. Michael named his son Wimiya after him.

The younger Wimiya is an actor and playwright who is also very knowledgeable in Yindjibarndi law. He read from the biography of Woodley King who established another independent community called Ngurrawana to educate young people in traditional life and law. Wimiya’s father Michael was one of these young people and he went on to lead the successful native title claim in 2021.

Woodley became the family’s last name at the whim of the registry office and these strange and cyclical slippages seem to blur the separation between the readers and their ancestors. Such slippages in naming were not uncommon as Aboriginal peoples became incorporated into British-Australian systems of nomenclature without their control or consent.

I also had the honour of working with Moonjah (Middleton) Cheedy who read from the biography of his uncle Johnny Walker – another name bestowed by a station master.

While I talked with Moonjah he showed me several repatriated objects from a Swiss collection. The first is a spear thrower that serves a double purpose as a musical instrument. It makes a rasping sound by rhythmically running a stick over the notches carved in its edge to accompany singing. Next is a box of punishment spears; of the kind that were put through the thighs of law-breakers. From their beautiful and imposing designs they were clearly valued artefacts. As well as being deterrents they represent the seriousness of traditional law.

As I talked with Moonjah, I realised that he was sitting under a picture of his father Ned. Ned Cheedy was one of the most significant Yindjibarndi elders. He conducted a cultural survey of the country collecting information and recordings that contributed greatly to the success of the Yindjibarndi native title ruling. In 2011 Ned Cheedy was recognised as Indigenous Elder of the Year.

It’s great to see the two together, one continuing in the footsteps of the other.

Images:

Lorraine Coppin gives a tour of Juluwarlu’s archive.

Stanley Warrie faces down the dead cat while reading from the biography of Yilbie Warrie.

The founding generation of the Cheeditha independent community.

Michael Woodley overlooking Yindjibarndi country and his son Wimiya Woodley at Naidoc.

Moonjah (Middleton) Cheedy with a spear thrower.

The repatriated punishment spears.

Moonjah (Middleton) Cheedy with a portrait of his father Ned Cheedy.